Androgen insensitivity syndrome

| Androgen insensitivity syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

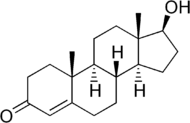

Testosterone (structure pictured) and dihydrotestosterone to a lesser degree, are the primary androgens involved in AIS. |

|

| ICD-10 | E34.5 |

| ICD-9 | 259.5 |

| OMIM | 312300 300068 |

| DiseasesDB | 29662 12975 |

| eMedicine | ped/2222 |

| MeSH | D013734 |

| GeneReviews | Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome |

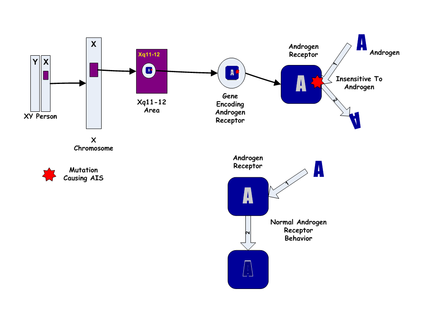

Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), also referred to as androgen resistance syndrome, is a set of disorders of sex development caused by mutations of the gene encoding the androgen receptor.[1] The set of resulting disorders varies according to the structure and sensitivity of the abnormal receptor. Most forms of AIS involve a variable degree of undervirilization and/or infertility in XY persons of any gender. A person with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) has a female external appearance despite a 46XY karyotype and undescended testes, a condition once called "testicular feminization" a phrase now considered both derogatory and inaccurate.

Since 1990, major scientific advances have greatly expanded medical understanding and management of the molecular mechanisms of the clinical features of AIS. Importantly, advocacy groups for this and other intersex conditions have increased public awareness and spurred acceptance and understanding of the variable nature of gender identity. The value of accurate and scientifically detailed information for patients is now emphasized, with physicians no longer automatically recommending traditional surgical corrections, with elective option now viewed as a possible but no longer necessary intervention for ambiguous conditions.

Incidence and genetics

The incidence of complete AIS is about in 1 in 20,000. The incidence of lesser degrees of androgen resistance is unknown. It's been suggested by various authorities that it could be either more common or less common than complete AIS. Evidence suggests many cases of unexplained male infertility may be due to a mild degree of androgen resistance.

Because the Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome gives rise to misleading between the genetic and the phenotypic gender, the convention is to designate a 46,XX individual as a genotypic female, and an 46,XY as a genotypic male. According to this convention, a person with Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome is a phenotypic female with a chromosomal genotype of 46,XY.

The Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome has been linked to mutations in AR, the gene for the human Androgen Receptor, located at Xq11-12 (i.e. on the X chromosome). Thus, it is an X-linked recessive trait, causing minimal or no effects in 46,XX people.

However, 46,XX women with a single mutated copy of the AR gene can be carriers of AIS, and their 46,XY children (genetically male) will have a 50% chance of having the syndrome. As in other X-linked recessive conditions, carrier mothers may display some minor traits of the condition; AIS carriers often have less axillary and pubic hair and a reduced incidence of normal acne during adolescence.

Most individuals born with AIS have inherited their single X chromosome with its defective gene from their mother and may have siblings with the same disorder. Generally, inherited mutations effect siblings similarly, though different syndromes may occasionally manifest from the same mutation. (Carrier testing is now available for relatives at risk when a diagnosis of AIS is made in a family member.)

Over 100 AR mutations causing various forms of AIS have been recorded. The milder forms of AIS (4 and 5 in the list below) are caused by a simple missense mutations with a single codon/single amino acid difference, while complete and almost complete forms result from mutations that have a greater effect on the shape and structure of the protein. About one third of cases of AIS are new mutations rather than familial. A single case of CAIS attributed to an abnormality of the AF-1 coactivator (rather than AR itself) has been reported.[2]

Normal function of androgens and the androgen receptor

Understanding the effects of androgen insensitivity begins with an understanding of the normal effects of testosterone in male and female development.[3] The principal mammalian androgens are testosterone and its more potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

The androgen receptor (AR) is a large protein of at least 910 amino acids. Each molecule consists of a portion which binds the androgen, a zinc finger portion that binds to DNA in steroid sensitive areas of nuclear chromatin, and an area that controls transcription.

Testosterone diffuses from circulating blood into the cytoplasm of a target cell. Some is metabolized to estradiol, some reduced to DHT, and some remains as testosterone (T). Both T and DHT can bind and activate the androgen receptor, though DHT does so with more potent and prolonged effect. As DHT (or T) binds to the receptor, a portion of the protein is cleaved. The AR-DHT combination dimerizes by combining with a second AR-DHT, both are phosphorylated, and the entire complex moves into the cell nucleus and binds to androgen response elements on the promoter region of androgen-sensitive target genes. The transcription effect is amplified or inhibited by coactivators or corepressors.

Although testosterone can be produced directly and indirectly from ovaries and adrenals later in life, the primary source of testosterone in early fetal life is the testes, and it plays a major role in human sexual differentiation. Before birth, testosterone induces the primary sex characteristics of males. At puberty, testosterone is primarily responsible for the secondary sex characteristics of males.

- See Testosterone article for fuller discussion of androgen sources and the role of testosterone in average human development.

- See Sexual differentiation for a brief but fuller overview of human sexual differentiation and biological sex differences.

Defects in the androgen receptor

The most common cause of AIS are point mutations in the androgen receptor gene resulting in a defective receptor protein which is unable to bind hormone or bind to DNA.[4]

Prenatal effects of testosterone in 46,XY fetus

In a normal fetus with a 46,XY karyotype, the presence of the SRY gene induces testes to form on the genital ridges in the fetal abdomen a few weeks after conception. By 6 weeks of gestation, genital anatomies of XY and XX fetuses are still indistinguishable, consisting of a tiny underdeveloped button of tissue able to become a phallus, and a urogenital midline opening flanked by folds of skin able to become either labia or a scrotum. By the 7th week, fetal testes begin to produce testosterone and release it into the blood.

Directly and as DHT, testosterone acts on the skin and tissues of the genital area and by 12 weeks of gestation, has produced a recognizable male, with a growing penis with a urethral opening at the tip, and a perineum fused and thinned into a scrotum, ready for the testes. Evidence suggests that this "remodelling" of the genitalia can only occur during this period of fetal life; if not complete by about 13 weeks, no amount of testosterone later will move the urethral opening or close the opening of the vagina.

For the remainder of gestation, the principal known effect of testosterone and DHT is continued growth of the penis and internal wolffian derivatives (part of prostate, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens).

Early postnatal effects of testosterone in 46,XY infants

Testosterone levels are low at birth but rise within weeks, remaining at normal male pubertal levels for about 2 months before declining to the low, barely detectable childhood levels. The biological function of this rise is unknown. Animal research suggests a contribution to brain differentiation.

Pubertal effects of testosterone in 46,XY children

At puberty, many of the early physical changes in both sexes are androgenic (adult-type body odor, increased oiliness of skin and hair, acne, pubic hair, axillary hair, fine upper lip and sideburn hair).

As puberty progresses, later secondary sex characteristics in males are nearly entirely due to androgens (continued growth of the penis, maturation of spermatogenic tissue and fertility, beard, deeper voice, masculine jaw and musculature, body hair, heavier bones). In males, the major pubertal changes attributable to estradiol are growth acceleration, epiphyseal closure, termination of growth, and (if it occurs) gynecomastia.

Variations produced by androgen insensitivity

Although many distinct mutations have been discovered, the spectrum of clinical manifestations has been divided into six phenotypes, which roughly correspond to increasing amounts of androgen effect due to increasing tissue responsiveness. It should be emphasized that some affected persons will have features that fall between the phenotypes described.

1. Complete AIS (CAIS): completely female body except no uterus, fallopian tubes or ovaries; testes in the abdomen; minimal androgenic (pubic or axillary) hair at puberty.[5]

2. Partial or incomplete AIS (PAIS): male or female body, with slightly virilized genitalia or micropenis; testes in the abdomen; sparse to normal androgenic hair.[5]

3. Reifenstein syndrome: obviously ambiguous genitalia; small testes may be in abdomen or scrotum; sparse to normal androgenic hair; gynecomastia at puberty.[6]

4. Infertile male syndrome: normal male genitalia internally and externally; normal male body or possible female androgyny, normal virilization and androgenic hair; reduced sperm production; reduced fertility or infertility.[6]

5. Undervirilized fertile male syndrome: male internal and external genitalia with micropenis; testes in scrotum; normal androgenic hair; sperm count and fertility normal or reduced.[6]

6. X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: normal or nearly normal male body and fertility; exaggerated adolescent gynecomastia; adult onset degenerative muscle disease.[7]

Complete AIS

People with CAIS are generally girls or women with internal testes, 46,XY karyotypes, and normal female bodies by external appearance with some exceptions. The vagina is not as deep, and there are no ovaries or uterus— hence no menses or fertility. Gender identity is usually female.

Symptoms of CAIS

If a 46,XY fetus cannot respond to testosterone or DHT, only the non-androgenic aspects of male development begin to take place: formation of testes, production of testosterone and anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) by the testes, and suppression of müllerian ducts. The testes usually remain in the abdomen, or occasionally move into the inguinal canals but can go no further because there is no scrotum. AMH prevents the uterus and upper vagina from forming. The testes make male amounts of testosterone and DHT but no androgenic sexual differentiation occurs. Most of the prostate and other internal male genital ducts fail to form because of lack of testosterone action. A shallow vagina forms, surrounded by normally-formed labia. Phallic tissue remains small and becomes a clitoris. At birth, a child with CAIS appears to be a typical girl, with no reason to suspect an incongruous karyotype and testosterone level, or lack of uterus.

Childhood growth is normal and the karyotypic incongruity remains unsuspected unless an inguinal lump is discovered to be a testis during surgical repair of an inguinal hernia, appendectomy, or other coincidental surgery.

Puberty tends to begin slightly later than the average for girls. As the hypothalamus and pituitary signal the testes to produce testosterone, amounts more often associated with boys begin to appear in the blood. Some of the testosterone is converted into estradiol, which begins to induce normal breast development. Normal reshaping of the pelvis and redistribution of body fat occurs as in other girls. Little or no pubic hair or other androgenic hair appears, sometimes a source of worry or shame. Acne is rare.

As menarche typically occurs about two years after breast development begins, no one usually worries about lack of menstrual periods until a girl reaches 14 or 15 years of age. At that point, an astute physician may suspect the diagnosis just from the breast/hair discrepancy. Diagnosis of complete AIS is confirmed by discovering an adult male testosterone level, 46,XY karotype, and a shallow vagina with no cervix or uterus.

Hormone measurements in pubertal girls and women with CAIS and PAIS are similar, and are characterized by total testosterone levels in the upper male rather than female range, estradiol levels mildly elevated above the female range, mildly elevated LH levels, normal FSH levels, sex hormone binding globulin levels in the female range, and possibly mild elevation of AMH. DHT levels are in the normal male range in CAIS but reportedly in the lower male range in PAIS. Interpretation of hormone levels in infancy is more complex and cannot be as easily summarized for this article. Androgen receptor testing has become available commercially but is rarely needed for diagnosis of CAIS and PAIS.

Adult women with CAIS tend to be taller than average, primarily because of their later timing of puberty. Breast development is said to be average to above average. Lack of responsiveness to androgen prevents some usual female adult hair development, including pubic, axillary, upper lip. In contrast, head hair remains fuller than average, without recession of scalp or thinning with age. Shallowness of the vagina varies and may or may not lead to mechanical difficulties during coitus. Although the testes develop fairly unexceptionally before puberty if not removed, the testes in adults with CAIS become increasingly distinctive, with unusual spermatogenic cells and no spermatogenesis.

Diagnostic circumstances of CAIS

Most cases of CAIS are diagnosed in the following circumstances.

- Prenatal amniocentesis discovers male karyotype not matched by ultrasound or obvious female appearance at birth.

- A lump in the inguinal canal is discovered to be a testis.

- Abdominal surgery done for repair of inguinal hernia, appendicitis or other reason discovers testes or lack of uterus and ovaries. Even in the absence of a visible inguinal lump, perhaps 1% of girls operated on for inguinal hernia are found to have AIS.

- Karyotype performed for unrelated purposes is found to be XY.

- The girl or family seeks evaluation for delayed menarche (primary amenorrhea).

- The woman seeks explanation for difficulty with sexual intercourse.

- The woman seeks explanation for infertility.

- Diagnosis of androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) is confirmed by identification of a novel homozygous nonsense mutation predicted to negatively impact androgen receptor (AR) gene function.[8]

Aspects of medical treatment of CAIS

The ethical aspects of diagnostic disclosure are: (1) the history of withholding information from patients with variations of reproductive development based on the assumption that physicians were better able to determine what was in the patient’s best interest; (2) the principle of informed consent asserts an ethical imperative to disclose such a diagnosis to the patient; in the case of minors, participation in decision-making is guided by the concept of “assent” commensurate with developmental capacity; and (3) the extent to which a physician has the dual responsibility to maintain confidentiality and to inform other members of the family that they may be at risk for being affected by a condition or for transmitting it to their offspring.

Others include: Accurate, sensitive explanation

- The need for explicit mention of such an obvious first step in the care of any disease or potentially undesirable medical differentiation reflects the difficulty felt by physicians in explaining testes to an adolescent girl, as well as the dissatisfactions with past medical care expressed by many women with CAIS.

Counseling, referral to support network

- Counseling should be included in published recommendations for CAIS management. Many women with CAIS find value in making connections with others similarly affected. The internet now provides some simple methods of connecting with such support (AIS USA Support Group (AISSG-USA)), (AIS UK Support Group (AISSG)), (Bodies Like Ours, Intersex Community Support Forum, AIS support sub-forum).

Vaginal enlargement

- For women for whom vaginal shallowness is a problem, enlargement can be achieved by a prolonged course of self-dilation. Surgical construction of a vagina is sometimes performed for adults but carries its own potential problems.

Gonadectomy decision

- Optimal timing of removal of the testes has been the management issue most often debated by physicians, though whether it is necessary has been questioned as well. The advantage of retaining the (usually intra-abdominal) testes until after puberty is that pubertal changes will happen "naturally," without hormone replacement therapy (HRT). This happens because the testosterone produced by the testes gets converted to oestrogen in the body tissues (a process known as aromatisation).

- The primary argument for removal is that testes remaining in the abdomen throughout life may develop benign or malignant tumors and confer little benefit. The testicular cancer risk in CAIS appears to be higher than that which occurs with men whose testes have remained in the abdomen, and rare cases of testicular cancer occurring in adolescents with CAIS have been reported. Unfortunately the uncommonness of CAIS and the small numbers of women who have not had testes removed make cancer risk difficult to quantify. The best evidence suggests that women with CAIS and PAIS retaining their testes after puberty have a 25% chance of developing benign (harmless) tumors and a 4-9% chance of malignancy.

- There is also the issue of whether medical advances might enable tissue from testes in situ to be used with a donor egg to produce a child via IVF that is genetically related to the XY woman. This chance is lost forever if the testes have been removed, unless they are in some way preserved; however, studies have shown that undescended testes are often incapable of producing viable spermatozoa, as the Sertoli cells which produce them cannot be sustained at the higher temperatures of the internal body - hence the presence and function of a scrotum in males. Apart from this, a significant number of CAIS women say that they never felt the same after gonadectomy as a young adult, that they lose their libido etc. Another benefit provided by testes in CAIS is the estradiol produced from testosterone. Although this can be provided pharmaceutically post-gonadectomy, many CAIS women have trouble adjusting to artificial HRT and regret losing their natural source of oestrogen.

Estrogen replacement

- Once testes have been removed, estrogen needs to be taken in order to support pubertal development, bone development, and completion of growth. Among estrogen preparations available, transdermal patches are gaining in popularity. Since there is no uterus, progesterone is not considered necessary.

Osteoporosis

- CAIS women appear to have a higher than average risk of thinning of the bones (osteoporosis) but possibly not with an associated tendency to increased fracture. The low bone density does not always relate to poor compliance with an HRT regimen or to the timing of gonadectomy. It has been speculated that the lack of androgen action might be a contributing factor since women with the partial form (PAIS) seem to fare better in this respect. More research is needed in this area.

Genetic counseling information

When a woman is diagnosed with CAIS or PAIS, referral to a genetic counselor may be warranted to explain the implications of the X-linked recessive inheritance.

- The mother of the woman with AIS is likely to be an unaffected carrier of the gene on one of her X chromosomes.

- A mother who carries the defect will, on average, pass it to 50% of her children, whether XX or XY. Those who are XX will be similarly unaffected carriers who can pass it to succeeding generations. Those who are XY will have the condition but, being infertile, cannot pass it.

- If the family is large, other members can be found who have or carry AIS. Many women with AIS will be able to identify affected maternal relatives such as aunts or great aunts.

- Carrier detection by gene testing is now possible.

A small percentage of new cases of AIS are due to new, spontaneous mutations, and the above information about the family is not applicable. See the section above for more genetic details.

A note on history and terminology

Case reports compatible with CAIS date back to the 19th century, when hermaphroditism was the technical term for intersex conditions. In 1950, Lawson Wilkins hypothesized that this condition might be explained by resistance to testosterone but hormones could not be easily measured, and even chromosomes were just beginning to be understood. In 1953 J.C. Morris suggested the term testicular feminization, and by 1963 most of the essential pathophysiology of complete AIS was suspected. However, as the relationship with the partial forms became worked out in the 1980s, physicians began to prefer the less confusing and more comprehensive term androgen insensitivity. In the 1990s and early 2000s, patient advocacy groups also supported abandoning the term "testicular feminization, " which is now considered inaccurate, stigmatizing and archaic.

In an outcome study from one of the institutions (Johns Hopkins Hospital) with the greatest experience with this condition. Of 20 adult women seen in the clinic over the last 40 years with CAIS, 14 agreed to participate in a questionnaire and examination to assess long-term outcome. Most of the women agreed with delay of vaginal surgery until adolescence or later, and many felt inadequately informed about the details of their condition.[9]

Reifenstein syndrome

Androgen receptor mutations associated with more intermediate degrees of androgen responsiveness can result in more intermediate degrees of masculinization before birth and obvious ambiguity of the genitalia. Of the five clinical forms of AIS described here, this is the only one likely to result in uncertainty about a baby's sex at birth, and the most likely to be diagnosed in infancy. The clinical diagnostic and management problems are those common to many other intersex disorders. Puberty can produce secondary sex characteristics of both sexes, though not fertility as the spermatogenic tissue requires androgen support as well as scrotal location. The amounts of androgenic body hair and breast development are variable.

Neonatal manifestations

As described above, the testes of a 46,XY fetus produce AMH and testosterone. In Reifenstein syndrome, as in CAIS, PAIS, and normal males, the AMH suppresses development of a uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper vagina. However, unlike CAIS and PAIS, fetal testosterone has a significant effect on the external genitalia, producing a phallus smaller than a typical penis but larger than a typical clitoris. The labioscrotal folds are almost but not completely fused in the midline of the perineum, producing a small perineal pouch termed a "pseudovagina". Instead of being on the tip of the phallus, the urethra remains in this pseudovagina of the perineum (a position termed a 3rd degree hypospadias). The labioscrotal skin flanking the pseudovagina remains less prominent than labia but less thinned, rugated, and fused than a scrotum. The testes usually remain in the abdomen but occasionally can be felt in the inguinal canal. This genital configuration has traditionally been referred to as a pseudovaginal perineoscrotal hypospadias (PPSH) and can occur in other intersex conditions.

Variants of Reifenstein syndrome occur with greater or less androgen sensitivity and correspondingly more or less genital masculinization. The common feature is that they have enough ambiguity that they are not simply assumed to be normal female infants, as is usual in CAIS and PAIS.

This most obvious differentiation, somewhat midway between male and female, nearly always leads to referral to a pediatric endocrinologist and a full genetic, anatomic, and hormonal evaluation.

Diagnostic issues

Evaluation of neonatal ambiguity is described in more detail in the intersex article. It typically consists of pelvic ultrasound to determine presence or absence of uterus and gonads, karyotype, and measurement of testosterone, DHT, AMH, and one or more adrenal steroids. Commercial androgen receptor assays have recently become available.

AIS is one of the more common forms of male undervirilization. Even after absence of the uterus and a 46,XY karyotype have been demonstrated, a number of other conditions, including Leydig cell hypoplasia, several uncommon defects of testosterone synthesis, and 5α-reductase deficiency which can produce similar genital anatomy must be excluded.

One of the most important aspects of evaluation of suspected AIS is the potential tissue responsiveness to testosterone, since future growth of the penis and other male secondary sex characteristics are dependent on it. After one or more injections of testosterone are given to the infant, measurable growth of the penis and noticeably increased erection frequency over the next two weeks suggests (though not infallibly) a capacity for further growth and virilization at puberty.

Apolipoprotein D (APOD, encoded by an androgen upregulated gene in genital skin fibroblasts) can be used to asses the transcriptional status of Androgen receptor (AR) (Appari M, 2009) www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19330472.

Aspects of management

The first major management decision is the sex of assignment: will the baby be a boy or girl? Assignment depends partly on predicting likely pubertal development, potential response of the phallus to testosterone, and likely outcome of surgical reconstruction attempts. The Reifenstein form of AIS can present one of the most challenging sets of decisions imaginable as parents and physicians try to choose the "least bad" of several undesirable options.

- Male assignment is usually followed by one or more operations in infancy by a pediatric urologist to completely repair the hypospadias, close the midline pouch, and (if possible) place the testes in the scrotum. Gonadal status and potential testosterone responsiveness is reassessed around age 12. Breast tissue can be removed surgically in adolescence if excessive. Gonads should be removed if scrotal placement is impossible. High dose testosterone replacement will sometimes achieve further virilization. An advantage of this choice commonly cited by parents is consistency with karyotype. A survey of adults brought up this way reported that nearly all were comfortable with the gender assignment made at birth and the sexual function of their genitalia, but many were dissatisfied with the size.

- Female assignment is usually followed by gonadectomy in childhood to prevent further masculinization, especially at puberty; sometimes by surgery to enlarge the vaginal opening and reduce clitoral size. Estrogen is replaced at puberty. This course has the advantage that future tissue sensitivity to testosterone is irrelevant for a girl. This course may involve fewer surgical procedures than male assignment and surgery, and may produce a better cosmetic outcome, but a higher percentage of women raised with early surgical repair describe impairment of sexual sensation or function.

- A third option has been advocated in the last decade by some: to tentatively assign male or female sex but postpone all surgery until the child is capable of communicating their own sex identity. This approach is intended to make it easier for a child to reject or confirm the gender assigned in infancy by parents and doctors, and to choose or refuse reconstructive surgery. Once the child has communicated clearly their own sex identity, it is crucial that the child's identity be respected both by the parents, physicians and therapists who are caring for the child. All steps should be taken to respect the child's own sense of self by being given access to all health care necessary to facilitate life in the sex the child considers most appropriate.[10] This is deemed by many in the patient advocacy and intersex communities as the best option, as it is believed to avoid unnecessary trauma during and after puberty as a result of the incongruity of their own gender identity and the surgically assigned sex.

Over the last 40–50 years, the second path, female assignment with reconstructive surgery in infancy, has been the course most often chosen by parents and physicians, and the hazards of this course are most familiar. Since 1997, male assignment with early surgery is increasing in popularity, and even the third course of delaying surgery is sometimes followed. Advantages and disadvantages of this course will become apparent over the next two decades. See the intersex article for more detail on this important management shift.

Yet another note on history and terminology

One might fairly call Reifenstein syndrome "even more partial" AIS, but when E.C. Reifenstein described the features of a new syndrome of male "familial hypogonadism" in 1947, it was not known that this condition was due to an abnormal androgen receptor and related to the female conditions of CAIS or PAIS. Additional familial intersex and hypogonadal conditions described by Lubs, Gilbert, Dreyfus, Rosewater, Walker, and others are now considered variants of the Reifenstein syndrome form of AIS.

Infertile male syndrome

Androgen receptor mutations have also been discovered in men with normal internal and external genitalia but infertility due to absence of sperm (azoospermia). Androgenic body hair is normal and gynecomastia uncommon. Some have mildly elevated testosterone and LH levels but this is not invariable. Several surveys suggest that androgen receptor mutations can be found in 30-40% of men with infertility due to otherwise unexplained oligospermia or azoospermia. AIS may also explain most cases of a rarer form of male infertility, the Del Castillo or Sertoli-cell-only syndrome.

Undervirilized fertile male syndrome (Mild Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome)

Some AR mutations with mildly reduced sensitivity cause mild undervirilization. These men have normally formed internal and external genitalia but often a small penis. Androgenic body hair may be sparser than unaffected relatives. Ejaculate volume may be reduced, though sperm density is normal. Few examples of this variant of AIS have been reported, but unlike the previously listed phenotypes, many of these men are fertile. Also, individuals with this condition may experience gynecomastia during puberty.

X-linked spinal and bulbar atrophy syndrome

Kennedy disease is an X-linked spinal-bulbar muscle atrophy syndrome associated with mutations of the androgen receptor. Like the other forms of AIS described above, it affects only males.

Since the neuromuscular disease was first described in 1968 many kindreds have been reported. Ages of onset and severity of manifestations in affected males vary from adolescence to old age, but most commonly develop in middle adult life. Early signs often include weakness of tongue and mouth muscles, fasciculations, and gradually increasing weakness of proximal limb muscles. In some cases, premature muscle exhaustion began in adolescence. Neuromuscular management is supportive, and the disease progresses very slowly and often does not lead to extreme disability.

Endocrine manifestations of this disorder are variable and only rarely include undervirilization of internal or external genitalia. In the majority evidence of altered androgen sensitivity is restricted to exaggerated or persistent adolescent gynecomastia, and the mildly high LH, testosterone, and estradiol levels characteristic of other forms of AIS. In other words, most people affected with Kennedy disease are relatively normal XY men with normal fertility and normal or minimally reduced virilization.

The distinctive AR mutation of Kennedy disease, reported in 1991, involves multiplied CAG repeats in the first exon. The mechanism by which this type of mutation causes neuromuscular disease, while complete insensitivity does not, is not yet understood.

References

- ↑ McPhaul MJ (December 2002). "Androgen receptor mutations and androgen insensitivity". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 198 (1-2): 61–7. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(02)00369-6. PMID 12573815.

- ↑ Online 'Mendelian Inheritance in Man' (OMIM) 300274

- ↑ Lee HJ, Chang C (August 2003). "Recent advances in androgen receptor action". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 60 (8): 1613–22. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-2309-3. PMID 14504652.

- ↑ Nitsche EM, Hiort O (2000). "The molecular basis of androgen insensitivity". Hormone Research 54 (5-6): 327–33. doi:10.1159/000053282. PMID 11595828.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Johns Hopkins University. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=300068. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Partial Androgen Insensitivity". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Johns Hopkins University. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=312300. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ↑ "Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Johns Hopkins University. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=313200. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ↑ "Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome – Ethical and Legal Implications of Genetic Testing". Gghjournal.com. 2009-12-06. http://www.gghjournal.com/volume23/3/ab03.cfm. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ↑ Wisniewski AB, Migeon CJ, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, et al. (August 2000). "Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: long-term medical, surgical, and psychosexual outcome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 85 (8): 2664–9. doi:10.1210/jc.85.8.2664. PMID 10946863.

- ↑ "Official Positions". Intersexualite.org. http://www.intersexualite.org/English-Offical-Position.html. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

External links

- Information

- androgen at NIH/UW GeneTests

- An Australian parent/patient booklet on CAIS

- The Secret of My Sex news article

- Women With Male DNA All Female news article at ABCnews.com

- Patient groups

- AIS Support Group AISSG (UK and International)

- AIS Support Group (US)

- AIS Support Group (Australasia)

- Intersex Support Forums (US and International)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||